[My thanks to C451 for his help on the history of this, JH].

One of the many consequences of the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 following the demise of Cromwell’s commonwealth was that the Church of England was restored to its position as the Established Church. In an effort to secure as much support as possible, Charles II summoned twelve bishops and twelve Puritan ministers to a conference at the Savoy Palace in 1661. The idea was to see how wide the bounds of Communion might be. It was good timing. The Bishops, after the experience of Cromwell, had learned something of where intransigence might lead, and the Puritans might, without him, be about to learn the same lesson.

The Book of Common Prayer had not been revised since 1604. It had been banned in 1645 and suppressed during the Commonwealth. The hopes that it might be possible to find a revised form of the Book which would command support from the Puritans were generally dashed; their breach of Elizabeth I’s wise injunction not to ‘make windows into men’s souls,’ ensured that. The Bishops would not agree to a Minister having the right to say who could and who could not receive Communion, nor would they agree to his having the right to refuse to baptise a child; the Church was either national, or it was sectarian. The sectaries went their way.

The Bishops took their stand on precedent:

“If we do not observe that golden rule of the venerable Council of Nice[a], ‘Let ancient customs prevail,’ till reason plainly requires the contrary, we shall give offence to sober Christians by a causeless departure from Catholic usage, and a greater advantage to enemies of our Church, than our brethren, I hope, would willingly grant.”

And they went on:

“It was the wisdom of our Reformers to draw up such a Liturgy as neither Romanist nor Protestant could justly except against.” For preserving of the Churches’ peace we know no better nor more efficacious way than our set Liturgy; there being no such way to keep us from schism, as to speak all the same thing, according to the Apostle. This experience of former and latter times hath taught us; when the Liturgy was duly observed we lived in peace; since that was laid aside there hath been as many modes and fashions of public worship as fancies.”

On 20 December 1661 the (fifth) revised Book of Common Prayer was approved by the Convocations of Canterbury and York and annexed to the Bill of Uniformity, which was passed by Parliament and received Royal Assent on 19 May 1662. There were few significant changes since 1604. On the whole, that settled things until the nineteenth century, which is not to say there were not the usual discussions among the learned and the interested (which two parties even sometimes coincided).

It is not often stressed that one of the most fervent defenders of the BCP was that great and good man, John Keble. The third of the Tracts for the Times, written by none other than Newman, argued that those who thought like him and Keble should petition the bishops to resist changes in the BCP being demanded by men like the famous headmaster of Rugby, Thomas Arnold. In the 1850s what was then called the “Broad Church” formed an association to press for changes in the BCP, but despite a series of bills tabled in the Lords, they got nowhere.

Inevitably the issue got caught up in the wider controversy over “Ritualism,” with those opposed to what they called the “Romanising tendencies” of the Oxford Movement. What was clear was that there were many in the Church who wished to keep it comprehensive, and in the words of one set of commentators:

“If, therefore, the Church of England is to remain the National Establishment of a free country, room must be found within it, as far as is consistent with general conformity ‘in such matters as may be deemed essential’.”

In 1872 the Archbishop of Canterbury managed to guide a short reform through the Convocations and Parliament sanctioned the changes, which were largely to do with making the services shorter. Its critics said that it would lead to chaos and accused Tait of what we would call “dumbing down”; truly there is nothing new under the sun!

The experience was not a happy one, and the issue would rumble on until the 1920s when a serious attempt at Prayer Book revision, complete with a new Book, was proposed – but the attempt to get it through Parliament failed – but as that is one of C451’s hobbies, I shall stop there.

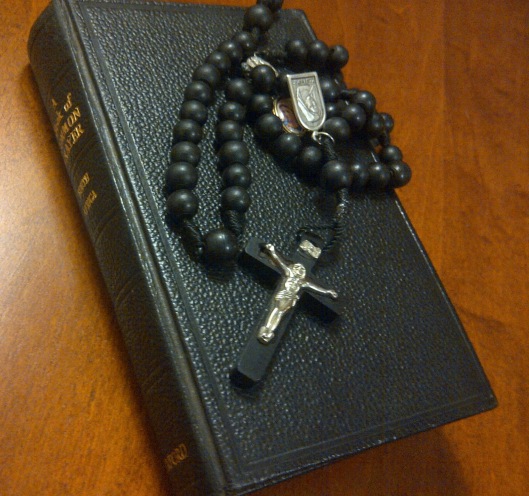

But what I hope this little excursus shows is that the Prayer Book has always been the focus of how Anglicans pray, a topic to which I want to return. On the one side its adherents have consistently rejected attempts to de-sacrilise our Liturgy and refused to water down the sacramental elements in it. On the other, they have resisted attempts to go the whole road to Rome route. It can be argued that in not using the Prayer Book as much, our Church lost something in terms of coherence, but that’s another argument for one more learned than myself.

I’ll finish simply by saying that it remains, for me, at the centre of my private devotions, but I also use “Common Worship” which I also find helpful. Anything that allows me to join millions of others in worshipping the Triune God is most welcome.

I was happy to be of assistance. Do persevere with your idea of a Lex orandi, lex credendi post.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I will – and thank you for yet more help – and at a time when I know you have so many more important things to do! xxx

LikeLiked by 3 people

As you know, I am delighted to see you back and always content to help.

LikeLiked by 3 people

My problem is with the Calvinistic tendencies in some of the Confessions and related documents.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, but Nicholas, you see Calvinism is everything, perhaps even here in my coffee.

I joke, of course, good friend.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Unfortunately I found some recently when I was researching historic premillennialism and stumbled into a pro-monergism site featuring articles by Reformed authors. And my favourite pre-wrath and post-trib authors are Reformed. I’d be safer with coffee…interestingly I haven’t had caffeine in weeks.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Well, I drink my coffee with no sweetener or sugar…it tastes like reprobation, so usually I might add a splash of milk for the elect.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’d be genuinely interested in what you mean here, Nicholas.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m referring principally to the Westminste Confessions rather than the BCP. For example, https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/creeds3.iv.xvii.ii.html

LikeLiked by 2 people

I see. I can’t say I have ever heard them mentioned in church.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Eg chapter 3:6 of the Westminster Confession.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree, but no one has ever asked me to affirm them!

LikeLiked by 2 people

But they are not part of the BCP. Indeed the 1661 Savoy Conference failed because the Bishops would not accept the Calvinists.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Delightful article! Very much enjoyed. Here, in churches that use the 1928 BCP, we often laugh that it is schizophrenic – the Rubrics can’t decide if we have priests or ministers, lol.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you very much Audre! I think the important thing is we do not have a separate clerical caste, something which has created so many problems for our RCC brothers and sisters xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love these, dearest friend. xx

Love the BCP, as well, both as a Christian and as a Lutheran. Like us, Anglicans are the bridge over the Tiber between Catholics and the Calvin/Hus led full-on Protestantism. But Cranmer writes in far better English, as did Tyndale and the compilers of the King James version.

For me too, the BCP is often my companion in private prayer, and while I also use the Lutheran Service Book to my benefit, I like the LBS, but love the BCP for what it is, but also as some of the best of English literature.

LikeLiked by 3 people

It is indeed, dearest friend – a source of inspiration and comfort xx

LikeLiked by 3 people

Very much so. Another of those things that I thank my dearest friend for bringing to me xx

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you 🙂 xx

LikeLiked by 3 people

🙂 xx

LikeLiked by 2 people