When the sun rose on 29 May 1453 Constantinople was still the capital city of the Roman Empire, as it had been since its foundation by Constantine in 3330; by the time it set it was the capital of the Islamic Empire ruled over by the Ottomans.

When the sun rose on 29 May 1453 Constantinople was still the capital city of the Roman Empire, as it had been since its foundation by Constantine in 3330; by the time it set it was the capital of the Islamic Empire ruled over by the Ottomans.

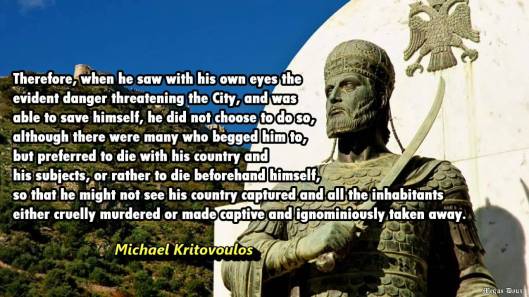

As the sun rose, the 5000 defenders looked out at the forces of Sultan Mohammed II, whose forces were at least fifteen times larger – and they included at least 30,000 Christians fighting for the Ottomans. Christendom’s division was reflected even within the doomed city. The Union of Florence of 1422 had settled the differences between the Catholic Church and the Orthodox, to the satisfaction of the former, but not the latter. Although the Emperor’s representatives had accepted the terms, some of the Orthodox representatives had not, and the reaction back in the city had been so hostile that no Emperor had dared to celebrate the new Liturgy. Constantine had always favoured the union, and with nothing to lose, he decided to go out in style. The Ottomans had offered Constantine XI honourable terms for surrender, but for the Emperor there was no such thing; it was not, he said, within his authority to surrender the imperial city; he would fight, and if need be, die defending his patrimony.

So it was that on the evening of 28 May, Constantine summoned his people together for a Liturgy in the greatest Cathedral of Christendom – the Cathedral of Divine Wisdom – Hagia Sophia. The Liturgy would include both Orthodox and Catholics, and would be celebrated according to the 1422 agreement. Even in this hour of supreme peril, there were those who refused to attend because of the ecumenical nature of the event. Those who survived the morrow would find there were worse fates.

The best pen portrait of that final evening of Christian Constantinople is that offered by Sir Steven Runciman in his The Fall of Constantinople; it deserves extended quotation:

‘In contrast to the silence in the Turkish camp, in the city the bells of the churches rang and their wooden gongs sounded as icons and relics were brought out upon the shoulders of the faithful and carried round through the streets and along the length of the walls, pausing only to bless with their holy presence the spots where the damage was greatest and the danger most pressing; and the throng that followed behind them, Greeks and Italians, Orthodox and Catholic, sang hymns and repeated the Kyrie Eleison.

The Emperor himself came to join in the procession; and when it was ended he summoned his notables and commanders, Greek and Italian, and spoke to them. …

Constantine told his hearers that the great assault was about to begin. To his Greek subjects he said that a man should always be ready to die either for his faith or for his country or for his family or for his sovereign. Now his people must be prepared to die for all four causes.

He spoke of the glories and high traditions of the great Imperial city. He spoke of the perfidy of the infidel Sultan who had provoked the war in order to destroy the True Faith and to put his false prophet in the seat of Christ. He urged them to remember that they were the descendents of the heroes of ancient Greece and Rome and to be worthy of their ancestors.

For his part, he said, he was ready to die for his faith, his city and his people …

All that were present rose to assure the Emperor that they were ready to sacrifice their lives and homes for him. He then walked slowly round the chamber, asking each one of them to forgive him if ever he had caused offence. They followed his example, embracing one another, as men do who expect to die.

The day was nearly over. Already crowds were moving towards the great Church of the Holy Wisdom. … Barely a citizen, except for the soldiers on the walls, stayed away from this desperate service of intercession. … The golden mosaics, studded with images of Christ and His Saints and the Emperors and Empresses of Byzantium, glimmered in the light of a thousand lamps and candles; and beneath them, for the last time, the priests in their splendid vestments moved in the solemn rhythm of the Liturgy.

Later in the evening the Emperor himself rode on his Arab mare to the great cathedral and made his peace with God. Then he returned through the dark streets to his Palace at Blachernae and summoned his household. Of them, as he had done of his ministers, he asked forgiveness for any unkindness that he might have shown them, and bade them good-bye.’

The following day he died defending his city.

The city was, of course, a shadow of its former self, and the hopes that the rest of Christendom might help had long been abandoned. Christians in the West had better things to do – although as the Habsburgs were to discover, a stitch in time might have saved nine.

It is fitting to remember the heroism of the defenders – now if only there were some lesson we might learn from the story.

In a way, the desecration of Hagia Sophia is like the Abomination of Desolation all over again…

LikeLiked by 3 people

Indeed – the story is a dreadful one

LikeLiked by 3 people

We should never forget that they have Rome in their sights too. The Arabs tried to take Rome in the 9th century.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Rome has resisted – and will continue to do so.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a shame it was turned into a mosque. I feel it would have been better to have torn the building down than to “convert” it for Islamic worship.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Currently it is a museum, but there is a push from pressure groups in Turkey to turn it into a mosque again.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Under Erdogan it is likely to happen.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, despite Turkey’s economic boom, he is a terrible leader. Collision course with the West and co-operation with Iran. Awful.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is a situation of great danger.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I expect him to turn on Israel one day too. The Mavi Marmara incident was a kind of opening salvo. But I would expect a kind of “friendly face” before that eventually as such posturing promotes the “Islamic democracy is good” propaganda message.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Indeed – there was a hope that it would be turned back into a church after Constantinople fell to the allies at the end of World War I.

LikeLiked by 3 people

There are, no doubt, numerous lessons we *could* learn. One might be that Christianity is never so securely rooted in a place that it cannot be defeated there. Another might be that, for the Church, no local defeat is terminal because she is catholic.

LikeLiked by 3 people

C, I know that this has nothing to do with your post, but do you know how Jessica is doing?

LikeLike

Email me your answer at jrj1701@gmail.com

LikeLike

She’s fine.

LikeLike

What might we learn? That there is an ebb and flow, pendulum swings some may say, to history. Heretics are applauded for a time, only to be imprisoned by others. These two articles on Constantinople and Iconoclasm may be of use to some.

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04301a.htm

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07620a.htm

LikeLiked by 1 person

chalcedon451, how can I contact you to send you a link to the answer I promised in the comments on your Fatima Centenary post?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can you post a link here?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, but I will read this post first…

Thank you!

LikeLike

That’s fine – thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

chalcedon451, because of a posting snafoo, I had to delete the post after copying it without changes and publishing again.

https://pilgrimsprogressrevisted.wordpress.com/2017/05/31/answering-chalcedon451-of-all-along-the-watchtower-on-the-church-of-rome/

LikeLike

I have replied in two comments so far, both awaiting your moderation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

chalcedon451, your comments are approved. You should be able to see them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks. I shall return to deal with the other points you make ☺️

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad I had the opportunity to read this.

Here is the link to my blog. The post is at the top, as it’s the last post published.

https://pilgrimsprogressrevisted.wordpress.com

Thank you, chalcedon451.

LikeLiked by 1 person