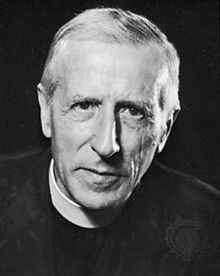

Whilst rummaging through some old note books earlier today I came across this beautiful quotation from Teilhard de Chardin’s Hymn of the Universe. Years ago he was recommended to me by the Anglican Chaplain to London University. At the time I was going through a period of doubt and uncertainty about God. I was seventeen when I went up to London to read for a medical degree at Guy’s . Here is the quotation.

” Since once again, Lord – though this time not in the forests of the Aisne but in the steppes of Asia – I have neither bread, nor wine, nor altar, I will raise myself beyond these symbols, up to the pure majesty of the Real itself; I, your priest, will make the whole earth my altar and on it will offer you all the labours and sufferings of the world.

Over there, on the horizon, the sun has just touched with light the outermost fringe of the eastern sky. Once again, beneath this moving sheet of fire, the living surface of the earth wakes and trembles, and once again begins its fearful travail. I will place on my paten, O God, the harvest to be won by this renewal of labour. Into my chalice I shall pour all the sap which is to be pressed out this day from the earth’s fruits.

My paten and my chalice are the depths of a soul laid widely open to all the forces which in a moment will rise up from every corner of the earth and converge upon the Spirit. Grant me the remembrance and the mystic presence of all those whom the light is now awakening to the new day.

(Page 19 of Hymn of the Universe.)

In the 60’s Fr Teilhard was much in vogue especially among Anglicans. A few years ago I made a pilgrimage to Clermont – Ferrand where he was born.

De Chardin was simultaneously a man of the earth and a man of God. His entire life was a continual study of, alternatively and together, the one and the other; geology and palaeontology on the on hand and, and philosophy and theology on the other. On both sides he made a valuable contribution to knowledge. However his unique and enduring achievement is to have brought earth and heaven together in a bold and imaginative and deeply realized synthesis. It was profoundly realized in the sense that it took account of all the facts and faced all the difficulties, theoretical and practical involved in his great enterprise.

At the time his views were largely rejected by his Church, but to-day there is further need to study them. His synthesis is very germane to the holistic, ecological, post- modern and global ideas of to-day. Fr Teilhard’s strong life and earth affirming spirituality is only rarely and fully grasped and comprehended. It is his spirituality above all, the strength and inspirational power of his spiritual vision that needs to be better known. It can give so much to so many and answer many question that thinking people are asking to-day.

The following is an excerpt from the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

“Teilhard’s attempts to combine Christian thought with modern science and traditional philosophy aroused widespread interest and controversy when his writings were published in the 1950s. Teilhard aimed at a metaphysic of evolution, holding that it was a process converging toward a final unity that he called the Omega point. He attempted to show that what is of permanent value in traditional philosophical thought can be maintained and even integrated with a modern scientific outlook if one accepts that the tendencies of material things are directed, either wholly or in part, beyond the things themselves toward the production of higher, more complex, more perfectly unified beings. Teilhard regarded basic trends in matter – gravitation, inertia, electromagnetism, and so on – as being ordered toward the production of progressively more complex types of aggregate. This process led to the increasingly complex entities of atoms, molecules, cells, and organisms, until finally the human body evolved, with a nervous system sufficiently sophisticated to permit rational reflection, self-awareness, and moral responsibility. While some evolutionists regard man simply as a prolongation of the Pliocene fauna – an animal more successful than the rat or the elephant – Teilhard argued that the appearance of man brought an added dimension into the world. This he defines as the birth of reflection: animals know, but man knows that he knows; he has “knowledge to the square.”

http://absoluteprimacyofchrist.org/critique-of-fr-teilhard-de-chardin-by-dr-dietrich-von-hildebrand/

LikeLike

“chacun à son goût” as the old saying goes. All I can say is that Pere de Chardin came into my life when I needed him. Your Von Hildebrand may not have understood him. Jealousy I daresay.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“In a period familiar with Sartre’s “nausea” and Heidegger’s conception of the essentially “homeless” man, Teilhard’s radiant and optimistic outlook on life comes for many as a welcome relief. His claim that we are constantly collaborating with God (whatever we do and however insignificant our role) and that “everything is sacred” understandably exhilarates many depressed souls. “

LikeLike

Von Hildebrand is in good company by the way: https://www.ewtn.com/library/CURIA/CDFTEILH.HTM

LikeLike

As I said “chacun à son goût”

We can always find supporters for our own views. Fr Teilhard was above all a man of prayer and his love for God shows especially in his Hymn of the Universe.

“To be pure of heart means to love God above all things and to see him everywhere in all things.” Pensees no 49

LikeLiked by 1 person

And what sort of God is this? As he wrote to Leontine Zanta:

‘As you already know, what dominates my interest and my preoccupations is the effort to establish in myself and to spread around a new religion (you may call it a better Christianity) in which the personal God ceases to be the great neolithic proprietor of former times, in order to become the soul of the world; our religious and cultural stage calls for this’

One might call him the father of new-ageism.

LikeLike

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin writes of his vision in a way that is akin to poetry of the soul. It is in the language of poetry he communicates both his reverence for the material world and his constant awareness of the spiritual.

In all his writings it is the man of prayer who speaks to us. Most of his detractors appear as lesser men without the depth of soul that manifests itself in Fr Teilhard.

“Give me to recognize in other men, Lord God, the radiance of your own face. The irresistible light of your eyes, shining in the depths of things, has already driven me to undertaking the work I had to do and facing the difficulties I had to overcome: grant me now to see you also and above all in the most inward,most perfect, most remote levels of the souls of my brother-men.

LikeLike

I’ve been down this path before. For the worshippers of de Chardin there are no proofs that will dissuade them. It matters not the credentials of the theologians that condemn his writings or the Church Herself who warned Catholics of his writings and reinforced those warnings about 20 years later. To you and the lovers of this ‘prophet’ there is no theologians within the Church who can be right unless they approve of the man, his noosphere and omega point. You clearly got mad and did not read the entire evaluation of Hildebrand or you would have had a clear eyed evaluation that the Church Herself agreed with. I think the Church’s professional theologians probably understood de Chardin’s writings quite well . . . but then perhaps you are more astute than they?

LikeLike

scoop, you’re just prejudiced.

LikeLike

No. I’m faithful to my Church. If you Anglicans want to follow him, I have no problem with that. But I would not like an uninformed Catholic thinking that the man is orthodox in his thinking.

LikeLike

Faithful to your Church? Don’t you mean faithful to your interpretation of your church? To many out-sjde observers it appears that your church is breaking up into various factions.

LikeLike

Scoop, you’re clearly banging your head against a wall here, but on the other hand you’re absolutely correct. Teilhard has been roundly condemned by the Catholic Church as a heretic.

While Malcolm is quite entitled to share his rosy views of Teilhard, recommended by an Anglican chaplain at a time when Teilhard was in enormous vogue (and incidentally Catholic religious brothers and sisters were leaving their vows in droves as a result of bad teaching from all directions!), he is unwise to rebuke you with his barbed comment, “faithful to your interpretation of your church.” I find that outrageous and misleading.

The condemnation of Teilhard de Chardin that you correctly quoted is the view of the Church. End of story.

LikeLiked by 2 people

But of course it isn’t the end of story. Fr Teilhard de Chardin will continue to challenge the Churches.

LikeLike

I think we have to be clear about the status of the Monitum of 1962, and I quote:

“Several works of Fr. Pere Teilhard de Chardin, some of which were posthumously published, are being edited and are gaining a good deal of success. Prescinding from a Judgment about those points that concern the positive sciences, it is sufficiently clear that the above mentioned works abound in such ambiguities. and indeed even serious errors, as to offend Catholic doctrine. For this reason, the eminent and most revered Fathers of the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office exhort all Ordinaries, as well as Superiors of Religious institutes, rectors of seminaries and presidents of universities, effectively to protect the minds, particularly of the youth. against the dangers presented by the works of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin and of his followers.”

This is not a condemnation of all his work, nor of him. He died in 1955, and whilst he had fallen under suspicion, he shared that fate with almost every Catholic thinker of the 19th and 20th Centuries, including Newman. It is studiously vague about precisely what the ‘serious errors’ are.

Just as Chou en Lai (I’m too old to use the new form) said it was too early to judge the effects of the French Revolution, so I suspect it may be too early to pronounce a judgment on Teilhard.

LikeLike

Perhaps the culminating moment of the integration of Teilhard de Chardin’s vision into mainstream Catholic theology was the pontificate of Pope Benedict XVI. Pope Benedict had a well-deserved reputation as a first-rate theologian with a keen intellect. Morever, Pope Benedict, like Teilhard, has a deep respect for the richness of the Catholic tradition. Further, as successor to St. Peter, Pope Benedict’s views carry extra clout even when he is not issuing formal papal announcements. This combination of intellect, respect for tradition and teaching authority carry a tremendous amount of weight and deference.

As such, it is important that Pope Benedict has been speaking glowingly of Teilhard de Chardin’s evolutionary theology for over forty years. It is important that Pope Benedict cites Teilhard de Chardin’s concept of the Noosphere as a central feature of the Catholic Mass. It is important when Pope Benedict talks about Teilhard’s vision of The Mass on the World of the cosmos as a living host. It is important when the Vatican hosts a conference on Teilhard de Chardin in 2012 and Pope Benedict cites Teilhard de Chardin as an example of the New Evangelization needed at the beginning of the Year of Faith.

This was from an article by Dan Burke.

“By now, no one would dream of saying that [Teilhard] is a heterodox author who shouldn’t be studied” – Fr. Federico Lombardi, Vatican spokesman (July 2009).

LikeLiked by 1 person

In Chapter 2 of his book “The Spirit of the Liturgy,” Pope, Benedict describes how Teilhard’s theological vision of Christ is central to the Christian liturgical and Eucharistic experience:

“And so we can now say that the goal of worship and the goal of creation as a whole are one and the same—divinization, a world of freedom and love. But this means that the historical makes its appearance in the cosmic. The cosmos is not a kind of closed building, a stationary container in which history may by chance take place. It is itself movement, from its one beginning to its one end. In a sense, creation is history. Against the background of the modern evolutionary world view, Teilhard de Chardin depicted the cosmos as a process of ascent, a series of unions. From very simple beginnings the path leads to ever greater and more complex unities, in which multiplicity is not abolished but merged into a growing synthesis, leading to the “Noosphere”, in which spirit and its understanding embrace the whole and are blended into a kind of living organism. Invoking the epistles to the Ephesians and Colossians, Teilhard looks on Christ as the energy that strives toward the Noosphere and finally incorporates everything in its “fullness’. From here Teilhard went on to give a new meaning to Christian worship: the transubstantiated Host is the anticipation of the transformation and divinization of matter in the christological “fullness”. In his view, the Eucharist provides the movement of the cosmos with its direction; it anticipates its goal and at the same time urges it on.”

FR Teilhard is far from finished or being end of Story.

LikeLike

Dear me. Talk about sowing confusion! In case Scoop or other Catholics fall into the new age honey trap here, the 1962 monitum on Teilhard is still in force. The fact that attempts to rehabilitate PART of the works of Teilhard have been made by SOME figures in the Church, the official judgment on his doctrinal error is still official Church teaching. Not opinion.

For any likely to be misled by this, I recommend this blog article, and if you happen to read Italian the entire article in the Osservatore Romano that it references:

http://eponymousflower.blogspot.com.es/2014/01/false-obedience-and-rehabilitation-of.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

If Pope Benedict XVI can support Teilhard de Chardin then there must be something wrong with the Catholic Church’s condemnation of him.

LikeLike

Oh, and in case the key points gets lost in all the rosy subtleties… is there anything about the phrase “dangerous ambiguities and serious errors” that is unclear? This, I repeat, is a monitem by the Church doctrine commission that is still in place.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So What?

“is there anything about the phrase “dangerous ambiguities and serious errors” that is unclear?”

No, but there are many issues in the teaching of Jesus that are not clear. One is free to make up one’s own mind. We’re not robots.

LikeLike

What is lacking is specificity. It would be a mistake to see the Monitum as a wholesale condemnation.

LikeLike

Gareth, I guess you must have problems with your New Pope. He seems to be changing things wholesale. It must be very confusing for you. You’ll soon be having women deacons and no doubt in time Women Priests,

plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ursula King’s biography of Teihard de Chardin is a fascinating book written in a style which makes a challenging subject seem quite understandable. King weaves the story of Teihard’s life around snapshots of his constantly maturing vision of God, the universe and mankind.

Known for his original concepts such as the ongoing evolution of both the universe and mankind towards perfection and the existence of a global network of self-awareness, Teihard was always regarded as a loose canon by the Vatican. Consequently, not much of his work was released during his lifetime except for those relatively few items which were privately published and distributed among a circle of his friends.

Since his death all his books and essays have been made available to the general public. Teihard nurtured close, supportive relationships with caring females and left many letters revealing the importance of these women in his life.

Although at times he is difficult to comprehend, there is no doubt that Teihard ranks as one of the most important thinkers of the twentieth century. The fact that he is recognized as a famous and respected scientist as well as a mystic greatly increases his significance.

Fr Teilhard’s story may just be beginning.

LikeLike

Thanks to all. Good discussion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I simply can’t be bothered responding to the “challenge” of Pope Francis remark. I don’t think about him very much as it happens. My main point of contributing here was that it is wrong to tell Scoop he is just being “faithful to your interpretation of your church.” I am simply pointing out, correctly, that the monitem on Teilhard is still in place, and Scoop is correct to say it is the view of the Church that Teilhard is unsound. That’s all.

This is why I don’t waste my time much on blogs any more: the errors take too much effort to correct. Good luck with it all, Scoop. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Loose canon” ? I don’t know if Teilhard was ever made a canon. but he was certainly a loose cannon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Been here before Gareth. For those who love the man it is like a cult and a beloved cult leader. There are no arguments to dissuade the ‘true’ believers of Tielhard.

LikeLike

Again, I fail to see why this is being presented as black and white. No doubt there were some, indeed may still be some who ‘worship’ Teilhard, though the use of such language smacks of Bosco on Our Lady, and myself, I would steer very clear of such loose usage; but each to their own. It would be good if someone would say which parts of T’s writings they dsagree with and why, but perhaps that takes more effort than throwing stones?

LikeLiked by 1 person

You need only to open the first link of the comments to get a very good review of what fell short in Teilhardism.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, but that is not the Monitum, and you are eliding the views of one writer on another with the views of the Church. Do you not suppose that if the Church had been of the same mind as the author of the piece it would not have written what he did?

I have no dog in this fight. Teilhard is an interesting writer and theologian. If I want to know what the Church thinks, I read the Catechism, but if I want to know how it got there, I read past theologians. Teilhard contributes to the ongoing journey of the Church through time.

The Orthodox Church is proud of the fact that no one seems to have had an original thought since God only knows when. A living Church has men and women in it inspired by the joy of the Faith to think and speculate. Life is good – a museum is not alive – and the Church is not a museum.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well I don’t think the specific problems are of much interest since in Teilhard’s own words he was creating a new and better Christianity. I have seen quotes of de Chardin that claimed that “God needs man more than man needs God” and that God is evolving basically; forgot the words he used. Now can you imagine trying to sit down and take perfectly good Christian sounding paragraphs because he uses the word God or Christ [his view of Christ was pretty weird as well] when he has something in mind which is not the God that is held by the Church. As far as the condemnations of his books and his teaching as a Catholic . . . those were revoked by the Jesuits first and the then on a number of occassions by the Church [prohibiting their publication] before the monitum was even written. It was a well known fact that the Church regarded his theology as incompatible to the faith. A simple monitum was all that was needed at the time but after Teilhard’s death his writings were flooding the market and he found a following and was not without friends among the Cardinals and other theologians such as Henri de Lubac.

Yes, the Church thinks that part of Her mission is answer questions and disruptive speculations by either incorporating the good as a development of the prior [purely organic] and to condemn the novel which is where Teilhard fits in. So if in the future people will be reading Teilhard for his introduction of novelty into Church teaching then we are in worse trouble than I thought. Von Hildebrand will endure but Teilhard found large popularity among Communists and Liberals of every stripe. I was not kidding about the cultish aspect of this: I have experienced in every discussion regarding him to the true believers in the man. They will not even read a condemnation of ideas and usually respond with ad hominems. It is typical of those cults such as the followers of Helen Schuck’s, A Course in Miracles. She didn’t have the staying power of Teilhard but her followers acted in a similar manner.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Scoop – You know old chap, you were invited to make a comment on my blog. But no, you posted a link to some fellow called von hildebrand.

Instead of contributing something worth while, you set about destroying the reputation and insights of a man who you will never equal.either in intelligence or inspiration. You acted like a bull in a china shop. Shame on you.

As for your friend Gareth Thomas, the less said the better.

LikeLike

” . . . some fellow called von Hildebrand.” His isn’t just some fellow, Malcolm. Here is how his profile begins on Wikipedia:

Hildebrand was called “the 20th Century Doctor of the Church”[1] by Pope Pius XII. Pope John Paul II also greatly admired the work of Hildebrand, remarking once to his widow, Alice von Hildebrand, “Your husband is one of the great ethicists of the twentieth century.” Benedict XVI also has a particular admiration and regard for Hildebrand, whom he knew as a young priest in Munich. The degree of Pope Benedict’s esteem is expressed in one of his statements about Hildebrand: “When the intellectual history of the Catholic Church in the twentieth century is written, the name of Dietrich von Hildebrand will be most prominent among the figures of our time.”

So if you want me to make a better and more qualified statement about the philosophy of Teilhard, I wouldn’t be able to. For this is from an eminent scholar that ws praised by 3 popes and admired by many theologians and will be for a long, long time.

Sorry that you don’t want expert opinion but only chit chat and superficial praise from readers. I’ll try to keep that in mind for the future.

LikeLike

Grow up.

LikeLike

Malcolm, please calm down. We are all friends here. And I can assure you we are all grown up.

LikeLike

Just saw this article. I wonder how many Rev. would read from the Koran, would you be one of them? Would Teilhard approve?

http://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/leave-dying-church-england-urges-former-queens-chaplain/

LikeLike

Steve Brown, Would I read from the Qur’an? No. I have the entire Bible to read from. In any case as an Anglican I understand the Word became flesh in Jesus and tabernacled among us.. The Koine Greek makes this very plain.

1 ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν θεόν, καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος.

2 οὖτος ἦν ἐν ἀρχῇ πρὸς τὸν θεόν.

3 πάντα δι᾽ αὐτοῦ ἐγένετο, καὶ χωρὶς αὐτοῦ ἐγένετο οὐδὲ ἕν. ὃ γέγονεν

4 ἐν αὐτῶ ζωὴ ἦν, καὶ ἡ ζωὴ ἦν τὸ φῶς τῶν ἀνθρώπων·

5 καὶ τὸ φῶς ἐν τῇ σκοτίᾳ φαίνει, καὶ ἡ σκοτία αὐτὸ οὐ κατέλαβεν.

6 ἐγένετο ἄνθρωπος ἀπεσταλμένος παρὰ θεοῦ, ὄνομα αὐτῶ ἰωάννης·

7 οὖτος ἦλθεν εἰς μαρτυρίαν, ἵνα μαρτυρήσῃ περὶ τοῦ φωτός, ἵνα πάντες πιστεύσωσιν δι᾽ αὐτοῦ.

8 οὐκ ἦν ἐκεῖνος τὸ φῶς, ἀλλ᾽ ἵνα μαρτυρήσῃ περὶ τοῦ φωτός.

9 ἦν τὸ φῶς τὸ ἀληθινόν, ὃ φωτίζει πάντα ἄνθρωπον, ἐρχόμενον εἰς τὸν κόσμον.

10 ἐν τῶ κόσμῳ ἦν, καὶ ὁ κόσμος δι᾽ αὐτοῦ ἐγένετο, καὶ ὁ κόσμος αὐτὸν οὐκ ἔγνω.

11 εἰς τὰ ἴδια ἦλθεν, καὶ οἱ ἴδιοι αὐτὸν οὐ παρέλαβον.

12 ὅσοι δὲ ἔλαβον αὐτόν, ἔδωκεν αὐτοῖς ἐξουσίαν τέκνα θεοῦ γενέσθαι, τοῖς πιστεύουσιν εἰς τὸ ὄνομα αὐτοῦ,

13 οἳ οὐκ ἐξ αἱμάτων οὐδὲ ἐκ θελήματος σαρκὸς οὐδὲ ἐκ θελήματος ἀνδρὸς ἀλλ᾽ ἐκ θεοῦ ἐγεννήθησαν.

14 καὶ ὁ λόγος σὰρξ ἐγένετο καὶ ἐσκήνωσεν ἐν ἡμῖν, καὶ ἐθεασάμεθα τὴν δόξαν αὐτοῦ, δόξαν ὡς μονογενοῦς παρὰ πατρός, πλήρης χάριτος καὶ ἀληθείας.

15 ἰωάννης μαρτυρεῖ περὶ αὐτοῦ καὶ κέκραγεν λέγων, οὖτος ἦν ὃν εἶπον, ὁ ὀπίσω μου ἐρχόμενος ἔμπροσθέν μου γέγονεν, ὅτι πρῶτός μου ἦν.

16 ὅτι ἐκ τοῦ πληρώματος αὐτοῦ ἡμεῖς πάντες ἐλάβομεν, καὶ χάριν ἀντὶ χάριτος·

17 ὅτι ὁ νόμος διὰ μωϊσέως ἐδόθη, ἡ χάρις καὶ ἡ ἀλήθεια διὰ ἰησοῦ χριστοῦ ἐγένετο.

18 θεὸν οὐδεὶς ἑώρακεν πώποτε· μονογενὴς θεὸς ὁ ὢν εἰς τὸν κόλπον τοῦ πατρὸς ἐκεῖνος ἐξηγήσατο.

19 καὶ αὕτη ἐστὶν ἡ μαρτυρία τοῦ ἰωάννου, ὅτε ἀπέστειλαν [πρὸς αὐτὸν] οἱ ἰουδαῖοι ἐξ ἱεροσολύμων ἱερεῖς καὶ λευίτας ἵνα ἐρωτήσωσιν αὐτόν, σὺ τίς εἶ;

20 καὶ ὡμολόγησεν καὶ οὐκ ἠρνήσατο, καὶ ὡμολόγησεν ὅτι ἐγὼ οὐκ εἰμὶ ὁ χριστός.

21 καὶ ἠρώτησαν αὐτόν, τί οὗν; σύ ἠλίας εἶ; καὶ λέγει, οὐκ εἰμί. ὁ προφήτης εἶ σύ; καὶ ἀπεκρίθη, οὔ.

22 εἶπαν οὗν αὐτῶ, τίς εἶ; ἵνα ἀπόκρισιν δῶμεν τοῖς πέμψασιν ἡμᾶς· τί λέγεις περὶ σεαυτοῦ;

23 ἔφη, ἐγὼ φωνὴ βοῶντος ἐν τῇ ἐρήμῳ, εὐθύνατε τὴν ὁδὸν κυρίου, καθὼς εἶπεν ἠσαΐας ὁ προφήτης.

24 καὶ ἀπεσταλμένοι ἦσαν ἐκ τῶν φαρισαίων.

25 καὶ ἠρώτησαν αὐτὸν καὶ εἶπαν αὐτῶ, τί οὗν βαπτίζεις εἰ σὺ οὐκ εἶ ὁ χριστὸς οὐδὲ ἠλίας οὐδὲ ὁ προφήτης;

26 ἀπεκρίθη αὐτοῖς ὁ ἰωάννης λέγων, ἐγὼ βαπτίζω ἐν ὕδατι· μέσος ὑμῶν ἕστηκεν ὃν ὑμεῖς οὐκ οἴδατε,

27 ὁ ὀπίσω μου ἐρχόμενος, οὖ οὐκ εἰμὶ [ἐγὼ] ἄξιος ἵνα λύσω αὐτοῦ τὸν ἱμάντα τοῦ ὑποδήματος.

28 ταῦτα ἐν βηθανίᾳ ἐγένετο πέραν τοῦ ἰορδάνου, ὅπου ἦν ὁ ἰωάννης βαπτίζων.

29 τῇ ἐπαύριον βλέπει τὸν ἰησοῦν ἐρχόμενον πρὸς αὐτόν, καὶ λέγει, ἴδε ὁ ἀμνὸς τοῦ θεοῦ ὁ αἴρων τὴν ἁμαρτίαν τοῦ κόσμου.

30 οὖτός ἐστιν ὑπὲρ οὖ ἐγὼ εἶπον, ὀπίσω μου ἔρχεται ἀνὴρ ὃς ἔμπροσθέν μου γέγονεν, ὅτι πρῶτός μου ἦν.

31 κἀγὼ οὐκ ᾔδειν αὐτόν, ἀλλ᾽ ἵνα φανερωθῇ τῶ ἰσραὴλ διὰ τοῦτο ἦλθον ἐγὼ ἐν ὕδατι βαπτίζων.

32 καὶ ἐμαρτύρησεν ἰωάννης λέγων ὅτι τεθέαμαι τὸ πνεῦμα καταβαῖνον ὡς περιστερὰν ἐξ οὐρανοῦ, καὶ ἔμεινεν ἐπ᾽ αὐτόν·

33 κἀγὼ οὐκ ᾔδειν αὐτόν, ἀλλ᾽ ὁ πέμψας με βαπτίζειν ἐν ὕδατι ἐκεῖνός μοι εἶπεν, ἐφ᾽ ὃν ἂν ἴδῃς τὸ πνεῦμα καταβαῖνον καὶ μένον ἐπ᾽ αὐτόν, οὖτός ἐστιν ὁ βαπτίζων ἐν πνεύματι ἁγίῳ.

34 κἀγὼ ἑώρακα, καὶ μεμαρτύρηκα ὅτι οὖτός ἐστιν ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ θεοῦ.

35 τῇ ἐπαύριον πάλιν εἱστήκει ὁ ἰωάννης καὶ ἐκ τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ δύο,

36 καὶ ἐμβλέψας τῶ ἰησοῦ περιπατοῦντι λέγει, ἴδε ὁ ἀμνὸς τοῦ θεοῦ.

37 καὶ ἤκουσαν οἱ δύο μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ λαλοῦντος καὶ ἠκολούθησαν τῶ ἰησοῦ.

38 στραφεὶς δὲ ὁ ἰησοῦς καὶ θεασάμενος αὐτοὺς ἀκολουθοῦντας λέγει αὐτοῖς, τί ζητεῖτε; οἱ δὲ εἶπαν αὐτῶ, ῥαββί ὃ λέγεται μεθερμηνευόμενον διδάσκαλε, ποῦ μένεις;

39 λέγει αὐτοῖς, ἔρχεσθε καὶ ὄψεσθε. ἦλθαν οὗν καὶ εἶδαν ποῦ μένει, καὶ παρ᾽ αὐτῶ ἔμειναν τὴν ἡμέραν ἐκείνην· ὥρα ἦν ὡς δεκάτη.

40 ἦν ἀνδρέας ὁ ἀδελφὸς σίμωνος πέτρου εἷς ἐκ τῶν δύο τῶν ἀκουσάντων παρὰ ἰωάννου καὶ ἀκολουθησάντων αὐτῶ·

41 εὑρίσκει οὖτος πρῶτον τὸν ἀδελφὸν τὸν ἴδιον σίμωνα καὶ λέγει αὐτῶ, εὑρήκαμεν τὸν μεσσίαν ὅ ἐστιν μεθερμηνευόμενον χριστός·

42 ἤγαγεν αὐτὸν πρὸς τὸν ἰησοῦν. ἐμβλέψας αὐτῶ ὁ ἰησοῦς εἶπεν, σὺ εἶ σίμων ὁ υἱὸς ἰωάννου· σὺ κληθήσῃ κηφᾶς ὃ ἑρμηνεύεται πέτρος.

43 τῇ ἐπαύριον ἠθέλησεν ἐξελθεῖν εἰς τὴν γαλιλαίαν, καὶ εὑρίσκει φίλιππον. καὶ λέγει αὐτῶ ὁ ἰησοῦς, ἀκολούθει μοι.

44 ἦν δὲ ὁ φίλιππος ἀπὸ βηθσαϊδά, ἐκ τῆς πόλεως ἀνδρέου καὶ πέτρου.

45 εὑρίσκει φίλιππος τὸν ναθαναὴλ καὶ λέγει αὐτῶ, ὃν ἔγραψεν μωϊσῆς ἐν τῶ νόμῳ καὶ οἱ προφῆται εὑρήκαμεν, ἰησοῦν υἱὸν τοῦ ἰωσὴφ τὸν ἀπὸ ναζαρέτ.

46 καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῶ ναθαναήλ, ἐκ ναζαρὲτ δύναταί τι ἀγαθὸν εἶναι; λέγει αὐτῶ [ὁ] φίλιππος, ἔρχου καὶ ἴδε.

47 εἶδεν ὁ ἰησοῦς τὸν ναθαναὴλ ἐρχόμενον πρὸς αὐτὸν καὶ λέγει περὶ αὐτοῦ, ἴδε ἀληθῶς ἰσραηλίτης ἐν ᾧ δόλος οὐκ ἔστιν.

48 λέγει αὐτῶ ναθαναήλ, πόθεν με γινώσκεις; ἀπεκρίθη ἰησοῦς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῶ, πρὸ τοῦ σε φίλιππον φωνῆσαι ὄντα ὑπὸ τὴν συκῆν εἶδόν σε.

49 ἀπεκρίθη αὐτῶ ναθαναήλ, ῥαββί, σὺ εἶ ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ θεοῦ, σὺ βασιλεὺς εἶ τοῦ ἰσραήλ.

50 ἀπεκρίθη ἰησοῦς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῶ, ὅτι εἶπόν σοι ὅτι εἶδόν σε ὑποκάτω τῆς συκῆς πιστεύεις; μείζω τούτων ὄψῃ.

51 καὶ λέγει αὐτῶ, ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω ὑμῖν, ὄψεσθε τὸν οὐρανὸν ἀνεῳγότα καὶ τοὺς ἀγγέλους τοῦ θεοῦ ἀναβαίνοντας καὶ καταβαίνοντας ἐπὶ τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου.

LikeLike

An arbitrary quantity of errors can be drawn from the work of any thinker; readers must take some responsibility in this regard. Regardless of issues with de Chardin, the lessons Malcolm took from his writing and the views he imparts in the post above seem consistent with Malcolm’s usual gentle orthodoxy. I’m sure everyone’s views are much closer than they appear. And the monitum is useful for those who, like me, are perhaps more curious than wise and might draw the wrong lessons from a casual reading.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Inflexible attitudes give Jesus a bad name. Orthodoxy can be a straight jacket and intolerable for the genuine seeker.

LikeLike

Maybe you should read a bit of Fulton Sheen and open your mind a bit Malcolm:

Click to access Plea-for-Intolerance.pdf

LikeLike

Hmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm.

LikeLike

“As for your friend Gareth Thomas, the less said the better.”

If I remember correctly, Jessica set up this blog as a response to being bullied on the Damian Thompson blog. The ad hominems here do you no credit Malcolm. I came here looking for some spiritual nourishment during this Lent. I find none. I have removed the Lent series I wrote for this blog last year, as I do not want my work seen alongside this claptrap.

Indeed, the less said the better.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Internet of Fools – Equus Asinus

What happened to the post after this one?

LikeLike

I think Chalcedon’s quotation from the Monitum of 1962 is very helpful. Saying that the works of TDC abound in ambiguities and errors is clear to me: it is not just one “banned” book, the CDF finds that the errors permeate TDC’s writings (there is no point in explicitly saying “omit pages 3, 7, 12, 19 to 25 inclusive, because they are heretical” so they simply say that too much of the egg is bad for it to be edible).

This is one advantage of the Catholic Church: it has experts who can decide whether a work is consistent with Catholic teaching (if it’s not, you are warned about it), rather than letting every amateur come to his own decision.

LikeLiked by 1 person