Tags

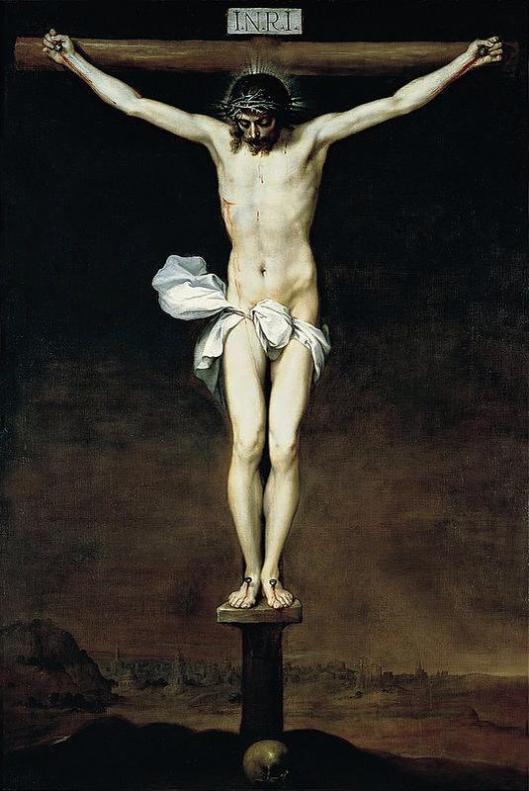

We need to remember that what we call justice and mercy are shadows on the cave wall, reflections of something so infinitely greater that we see it best in the blinding light of Calvary – where He forgives and asks the Father to forgive those who nailed him to the tree, and where, in extremis, he forgives Dismas. What is this love? It blinds us, it overwhelms us, could we get anywhere close to it when we get cross and sulk over goodness knows what slights?

The woman taken in adultery is guilty. She’s worse than a whore, she’s an adulteress and everyone knows what she ‘deserves’. We seem to need to presume she is repentant, but where is the sign of that? We know she ought to be, so we put it there for our comfort. The writer did not do that.

Instead he makes us confront something which makes us uncomfortable – Jesus, the only one who could justly have judged her, for he alone there was without sin, refuses to. He bids her sin no more.

What are we meant to take away from this? First we have to read it in that blinding light of Calvary and the Resurrection – which made all things new. It raised us from our sins, not by convicting us of them and then demanding repentance – but by forgiving us in love and then – and then what? And that’s where it gets scary for the elder brother and the Pharisee in all of us, because the other side of that is our desire that there should be justice and order and reparation, and it offends both our sense of these things, and of what God wants, to talk about forgiveness in the absence of confession and repentance – what on earth would follow from people getting the idea they are forgiven, why, they’d surely just carry on sinning?

Would they? Don’t we anyway? It isn’t like we say the sinner’s prayer, or go to Mass, or whatever and then we never sin again. We’re like Paul, we’re running the race. We don’t want that prize to go to someone who isn’t struggling to work in the vineyard we entered at the beginning to the long and toilsome day – our sense of justice says it isn’t right they should get what we get if they come for the last hour. There’s that shadow on the wall – we think, we know, the Church says (or we say it does) – but what does God say? What is his mercy? It extends to us. I don’t deserve it. If I have repented, I will sin again, and again, and be reconciled, and so on and again – there is no health in me save what I have from him. So who am I to complain if someone with sincere repentance comes to Him at the last, having been forgiven, but never having repented before. Am I the Just Judge?

Repentance matters, but the process by which God’s love and the Spirit draw it from our hard hearts is a great mystery and one to stand in awe of – for if we confess his name, it has already been drawn from us. Are we jealous children that we think Grace rationed so that if that sinner over there gets it, this miserable sinner here gets less? We speak as we find, we see Grace as we can, but we don’t see it as God can, we are not God. If being forgiven took hold in the adulteress’ heart and led her to immediate repentance, good, marvellous, but we’re not told that. How convenient and reassuring if the passage had ended with the words ‘and she did, indeed, go and sin no more’. Except it wouldn’t be reassuring, it wouldn’t speak to us where we are – we’d know it wasn’t true. So why would we find it so hard to take that we insist that there must have been repentance? Maybe she repented later, maybe on her death-bed, we don’t know, and why should we know. We know what we are told – she was a dreadful sinner caught in the act, and God did not judge her.

In our fear we think, perhaps, but how dreadful, women will get the idea they can go off and commit adultery – as Chalcedon’s commentary showed, that was just what some Christians leaders thought. We know some of the earliest heresies concerned the idea that if you were forgiven, you would think you could go and do what you like – but then such ideas never die, they come from sin, and we should not think we can suppress them – we can confront them in the blinding light of Calvary and see them for the sin they are – and try to have the faith that God knows what he’s doing and does not actually require our advice – just our love and faith.

Why is it always left up to me to introduce points of contention? I’m just lucky I guess.

Jess, I do not want to open a can of worms here, my friend, but there is much subtlety occurring in the shadows as well. So just a few different ideas to ponder.

Dismas (the good thief; i.e. the repentant thief) states a double confession. First he confesses that Christ is what He claims to be and second that both he and the other thief are deserving by their transgressions to suffer and die (admission of guilt). Christ’s love (or the Father’s love) comes first; of course, and it always does. This does not mean that forgiveness is automatically given without a change of heart by the penitent. Note that the bad thief (who did not confess but blasphemed) was not given any forgiveness. So mercy and forgiveness is obviously not automatic. It requires of movement in the heart of the offender.

Likewise, the other examples:

The younger son (or perhaps the Northern Kingdom of Israel) that swerved into idolatry and was considered to be adulterous is welcomed back into the household (or Judea, the Southern Kingdom) after confessing (at least in his heart) that “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired hands.” This is repeated as soon as the Father greets him. The two Kingdom interpretation was typed (in Ezek. 37:21-23 and Hos. 11:1-3, 11) as a welcoming into the New Covenant; a covenant of love. The parallel is best seen in Jer 31:18-20 where Ephraim repents his sin and returns from exile.

The woman caught in adultery is troublesome only because we want it to become fully about an act of forgiveness without repentance. It shows that Christ is both merciful and abides by the law. He did not overturn Moses Law and He did not defy Roman Law. But the accusers were left in the same trap they set . . . and therefore walked away . . . so that they would not have to be condemned by one law or the other. “Go and sin no more” is, as you say not a confession of any sort but it is a recognition by Christ that she was guilty of sin and that a change of heart . . . to sin no more against God was required of her. So Christ, it is assumed, moved her heart to repentance. At least if she attempts to sin no more and fails, she has means, through repentance to find forgiveness in love (if not in the Law).

It seems that there are as many ways to read scripture as there are people . . . but I still see that we (the sinners) must do something; even if it just throwing ourselves on God’s mercy (which is a confession of guilt and belief as well).

LikeLiked by 4 people

Not sure what the contentious point is – unless one of us is suggesting that God’s Grace can only ever work on one model?

I don’t think anyone is suggesting repentance does not matter and must not be part of the process – just that God can proceed as the Spirit listeth.

We are not told whether the woman repented, nor are we told whether she tried to sin no more. What our own experience tells us is that we repent and sin again, and so it seems a safe guess that even if she repented, she did not actually go away and sin no more. If sinning no more was necessary in practice, none of us would be saved. That was why Constantine waited until his death bed before becoming a Christian.

Certainly Dismas acknowledged Jesus was Lord and that he was a sinner. We never actually hear his confession, and if there is a baptism, it is one of desire, not water. It suggests, of course, that there is no need for any church or theology, just a Bosco-like acknowledging one is a sinner and Christ is Lord.

Protestants don’t make things up, they just see them from a different angle from the RCC, but then so does the Orthodox Church.

In the end, God alone knows how His Grace reaches us and what is in each of our hearts.

I hope that’s not contentious? 🙂 xx

LikeLiked by 2 people

Of course no, dear friend.

I suppose, that given the prayer of Christ from the Holy Cross to “Forgive them, for they know not what they do.” is analogous to the Catholic teaching of ‘invincible ignorance’ and thereby contains the ‘wideness’ of God’s mercy. However, since Christ has tasked the Church to teach the Gospel to all nations, I doubt that He would like us to get to heaven via the road of ignorance . . . though many might. It seems that knowing right from wrong and knowing when we fail to do right is why we are called to teache the nations. It is so that we can stand, once again, seek God’s mercy through a repentant heart and hopefully receive His Mercy and forgiveness. This is why I am reluctant to give those who stand far off from the Church the reassurance that they are OK without undergoing a baptism; dying with Christ and rising with Christ (dying to sin and living in righteousness) whether it is by water, desire or blood. And indeed His Grace is always trying to reach us: even if the first knowledge of Christ and His love is presented by the laity who may not know a whole lot more than those who are not Christians at all. In today’s world it is getting very hard to find the Teachings due to the vast amount of smoke that has obscured it. Now, it seems, is the time for the laity to be taught so that when children ask each other things about what they believe, a sound answer might inform the other and they will have no misgivings that there is a God of Mercy and that we are sinners not worthy of of His Goodness or Forgiveness. But that, by the Mercy of God, He left us the power to hear one’s confession and absolve the sinner of their sins. Yes . . . by invincible ignorance it is possible to recieve such a blessing . . . just like Dismas, there are those who do not come to Christ via they way that He has prescribed. There was no ordinary water baptism, as you say, and no formalized confession but it is clear that there was a realization of Who Christ was and who he was (a poor sinner); faith, hope and charity were not lost on the good thief. 🙂 xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do understand that, but we need to remember nothing we do ‘merits’ salvation. We say, easily, that we must repent, as though that were a magic formula which, once said, gets us to heaven – but I don’t think any of us, if it is put that way, would agree.

I think if we all said that we need to say Christ is Lord and that we acknowledge our sin, as the road to salvation, every church would be out of business – or at least fear it would be. In fact I doubt it, because if you come to know God, you want to worship him in love.

I do think we are far too fearful, far too defensive, and far too lacking in faith in the Holy Spirit. It isn’t up to you or me or anyone to assure anyone that they are saved – God knows that, and by Grace, if we come to Him, the way will be shown to us.

We must, I think, stop treating the uncatechised and unconverted as though, unless they understand complex distinctions, they cannot be saved. They can be saved in the twinkling of an eye. That’s the beginning, not the end of the process. If we know him, he will lead us – and we follow, even though we do not know the way.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I guess the magical is not that which most believing Christians teach or even think; as that seems more the mode of those who are unschooled in Christianity. But I will at that God’s love is a mystery beyond compare.

When I was a lad, I had friends of many faiths. Thereby, because kids are naturally inquisitive, we learned what the Catholics believed and certain protestants believed and it was shared, imperfectly to be sure, but the general idea that Christ is Lord and that sin harms no only our love of God but love of self and love of others was pretty much a given. It seems to me we had fuller churches then than we do at present.

Of course we want to Worship God in love and I don’t know anyone who believes that doesn’t. Our fear of failure is the fear that we offended someone Who is Love itself. It is filial fear and it is a good trait for Christians to bear.

These ideas are not complex distinctions in my mind as I understood them as a child. And of course other miracles can happen as occurred in my own wretched life . . . where Christ assailed me in conscience and word when I least expected it. And as you say, it is then a part of a process . . . a perfecting of conscience and a training of the will to abide by that well formed conscience. All of this has been given to us due to the wisdom and the mercy of God. He did not leave us ophans but has nursed His Church along to provide for us a place where we can heal when we hurt, love in a way that is no longer an act of narcissism but is instead a self-sacrificing love.

To know Him is to have Him lead us. Absolutely. The best way to get to know Him is in the Bibile and in the teachings of the Church which was established for that very purpose and as sign that will point people on the way. It errects warning signs for dead ends and arrows to encourage our taking the right path when other paths converge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree – but we shan’t on the definition of the Church. God knows its true boundaries and members.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m speaking of it’s Divine nature and not its human nature and in my mind the teachings are of its Divine nature; that which was given us from the Head of the Mystical Body of Christ and that which was revealed by the Holy Spirit He gave Her. So I would think that we are in agreement here as well. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

True, but in this instance I don’t quite see what the point of contention is.

LikeLike

If we read the Gospel on the woman taken in adultery, we can read into it what we want, but it nowhere states she repented, or that she did sin no more. Jesus did not condemn her – this was such a problem to the early Church leaders that they left it out of John’s Gospel.

We need to be humble and acknowledge that neither we, nor Latin phrases, nor legal distinctions, nor anything else delimits God’s mercy.

How like the elder bro we all are, how like the workers in the vineyard who have been there all day – we are not meant to take away the idea that we are right when we feel that way.

LikeLike

We agree. You see things in a complicated way and insist on distinctions which seem to you to be necessary. I simply say Love precedes everything and is the source of our salvation – we can do nothing to deserve that – even repenting does not merit salvation.

LikeLike

Jesus thought the Spirit rather more important – as did Paul. That is not to say it does not matter, it is to say it is subordinate to love. I do not see that insistence of the distinctions of the law save anyone – I do see it stops many from asking questions or exploring the faith more.

Some, I fear, seem to see the church as a club with rules – if we know God, and his love, we will come to the church and we shall obey the rules. I know no one who thinks the law saves.

LikeLike

If you know God’s love, you will want to try to follow the Law – if you don’t, you won’t be able to follow the Law, and if you assume that if you can follow the Law, you will come to God, you may fall away altogether.

Things come in order. If you love God and know his love, the other things will follow – you can know all the Law and follow it, you can know all doctrine and think you follow it – and you can be lost as lost can be.

LikeLike

No one said anything to the contrary. This is why I get puzzled.

You offer a very RC view, fine, you are an RC, to others this means nothing and sounds legalistic; I don’t say they are right, indeed, I say they are wrong – but I do say that that method is not a good one for bringing people to Christ.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It does, but we must not let that occupy centre stage – we are not saved by our brains!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, what I meant wasn’t anything very deep or to be taken for more than its simplistic reasoning; which was that we each informed our consciences by the reading of the same examples from Scripture but with differing understandings as to what Christ was showing us. That is about as contentious as I was being. It was more a comment on the lack of comments for a post that I thought was worthy of exploring in more detail. Nothing more, nothing less. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

In which case, happily, dear friend, we agree 🙂 xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thought we might. 🙂 xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

I find that hard to believe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve no problem with that. I only ever have a problem when we think we can tell how the Grace of God works – we received freely, and we should be grateful and not presume to say that sinner over there can only come to God as we did 🙂

LikeLike

No one has, and that’s what puzzles me – why should anyone suppose I had. Repentance is a complex phenomenon, and God reads our hearts and minds. He is the Just Judge, he alone knows – and if we think we do, we sin.

LikeLike

I think you are making those legalistic distinctions Jesus condemns here. If we are saved through mercy, we are forgiven – unless you think otherwise – which would be an interesting position.

LikeLike

Mercy comes from Love, which precedes it and forgiveness. Mercy can lead us to repentance, or we can repent first – God seems not to mind terribly much. God makes nothing complex – we make it complex.

I doubt a single one of the first Christians came to God because they were persuaded by the complexity of anything. Complex tells us man is involved – simplicity is of God.

LikeLike

The NT is actually very short, and the conditions for our salvation even shorter. God loves us, Christ died to atone for our sins, and if we acknowledge him Lord, we are sealed with his blood. Seems pretty simple to me.

LikeLike

But see what the Lord sayeth to sum up his message, and in what the Law and the Prophets are summarised – love of God, love of neighbour – everything else is a commentary and an illustration.

LikeLike

If you have not love, none of the rest will mean anything.

LikeLike

I’ve no wish to be contentious either, but a note on terms, might be in order. It seems to me that we are conflating mercy with grace, and likely we shouldn’t.

Mercy is defined as: “compassion or forgiveness shown toward someone whom it is within one’s power to punish or harm.” In the case of the law (secular or God’s) it is the antithesis of justice. And thank God for that, I say.

But God’s Grace, which gives us the power to repent, and receive, mercy is different, it is defined as, ” the unmerited favor of God toward man.”

Maybe, and I tend to use them as synonyms as well, that is part of the reason we get bogged here, time and again. Because they are not the same thing at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes good sister Jess, if they say something in Latin that makes it a gods honest truth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jessica – I think you might be nearer the mark if you try quoting ‘But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you’ or

Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse.

Do not take revenge, my dear friends, but leave room for God’s wrath, for it is written: “It is mine to avenge; I will repay,” says the Lord. 20 On the contrary:

“If your enemy is hungry, feed him;

if he is thirsty, give him something to drink.

In doing this, you will heap burning coals on his head.”

Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.

You do not know what God will ultimately do. You take the example of the woman in adultery. Apologies – I brought that up, but it is a bad example. Serious sin is where one person inflicts real harm on another. In this example, though, perhaps Jesus was giving her room to repent? The passage does not give a direct answer the question: what would happen to her on the day of judgement if she didn’t.

What you can write about is what our attitude should be. Matthew5v44 and Romans 12 state it explicitly.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think repentance, real repentance is a mystery – but the key to it is opening our hearts – not closing our minds.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jessica – that (of course) is a truism; I don’t think there is anyone who would disagree with that statement.

In Scripture, you do find very different expressions of love. For example, I find the writing style of the apostle Paul in some parts of 1 Corinthians highly entertaining; he is berating them – and he clearly can’t believe what is going on there. He’s a better man than me; if I see the sorts of things going on in a church which Paul doesn’t like, I tend not to confront them, but instead quietly note that this isn’t my kind of place and I leave. Paul continues to take an interest in them; when he berates them, it is an act of love.

As far as the woman taken in adultery goes (the example you gave): we aren’t given much details, but it doesn’t seem to me that there is anybody among the crowd who is devastated because he is a wronged husband of this woman; they simply took the case to Jesus because they were trying to score points. There was clearly nothing in their approach that looked like an act of love; clearly they were not trying to do their bit to put a sinner back on the the straight and narrow way.

In general, though, consider the example I gave earlier of one professor who tries to sack a lecturer, by manufacturing a fictitious budget crisis, on the last-in-first-out principle – just so that he can open a lectureship for his girlfriend (who is also his Ph.D. student) once it is all over. Now – if we are sickeningly and sanctimoniously nice to this professor, by so doing, we can end up urinating from a great height on the fellow whom he was trying to sack. He has to take the consequences of his actions (which are that he himself is dismissed from his job) – there is no alternative to this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Salvation is only a mystery to the unsaved.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bosco – I am saved – and Salvation is a great mystery to me – namely why on earth God would want me among the number of the Saviour’s family. He does; it is a great mystery why.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are lots of definitions of love, and in your example you offer up one of the most difficult. If the authorities will do nothing, then you lose your job and how do you forgive, as Jesus tells you you must, those who have despitefully used you?

I have recently lost my job – and the home that was to go with it, because of a last minute change of mind by my employer. It turned out that under HR laws because they had made offers orally but not in writing, I had no right of appeal – had it not been for a good friend, I’d be homeless and jobless – because some high official took the decision that they had someone who would suit them better – but he had not been available when the verbal offers were made to me.

My non-Christian friend has treated me better than my Christian employer, and I’ve managed to find a two day a week job after Easter. I could hate the people who did this to me, but I refuse to give them space in my head. If they can live with what they did, my resentment will simply infect my life – the people concerned are not worth that. So I have forgiven them, and I pray for them. But I will not work with them again – even were they to ask.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Much of what you write resonates – some of those who have perpetrated the worst against me were serious Christians.

I’m interested in what forgiveness means. How do you know if you have actually forgiven somebody? What does forgiveness entail?

LikeLiked by 1 person

For me it involved telling God in prayer that I forgave them, and then praying for them. I then let it go. The easy thing would been to have held on to what I could have called righteous anger. But what’s the point of letting that poison my life. I asked God for strength to forgive these sinnets as I am forgiven; he gave mr that Grace.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Jessica – in the case that I am thinking of here, I get the impression that the victim (i.e. the fellow facing the sack) has made a much better job of forgiveness than those of us who saw the whole thing from the sidelines.

In some sense I understand what you are saying, but I’m still left unsure of what forgiveness entails when one is dealing with people who are utterly unrepentant.

I’m sure that true forgiveness can’t mean leaving it for the Lord to avenge – and hoping that he does. Yet, when the fellow who was head of department at time died 10 years later of a painful stomach cancer, to my shame I was quite happy to hear the news. The victim (an atheist as far as I understand) was appalled at my attitude.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It isn’t about revenge at all – if one harbours such feelings, it is a sign that you have not forgiven – of that I am sure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True – and therefore our ability to forgive others is ultimately a gift from God. I think we all understand what Scripture says and means – and what we should aspire to. I don’t see many, not even among serious Christians who know what they are striving for who actually do.

I think you’re a Barthian. Even though he saw and lived through the worst horrors of Nazi Germany, yet Karl Barth seems to have been quite happy to believe that ultimately all are saved.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m simply happy to leave it to God – above my paygrade who goes to heaven.

LikeLike

I’m not – there are some people, who described themselves as atheists, whom I liked, who seemed to have a social conscience, great company, and wouldn’t hurt anybody (except perhaps for themselves – one whom I have in mind was an alcoholic and died reasonably prematurely as a result) and I’d be unhappy not to see them there.

There are other people, who described themselves as serious Christians, but who committed the worst acts and never repented of them – and I’d shudder at the thought of having to share the heavenly kingdom with them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I find it easier to leave it in God’s hands – it’s there any way 🙂

LikeLike

May the God of St Patrick forgive us our trespasses as we forgive others … http://biblestudyforcatholics.com/patrick/

LikeLiked by 2 people

http://biblestudyforcatholics.com/patrick/

biblestudy for lefthandedpeople.

biblestudyforvegetarians..

LikeLike

Among Benedict’s concerns are the belief that other religions are equal to Christianity in obtaining salvation and the change in dogma that lessens fears that one’s eternal salvation can be lost.

“The missionaries of the 16th century were convinced that the unbaptized person is lost forever,” Benedict said. “After the [Second Vatican] Council, this conviction was definitely abandoned. The result was a two-sided, deep crisis. Without this attentiveness to the salvation, the Faith loses its foundation.”

Breaking News at Newsmax.com http://www.newsmax.com/Newsfront/pope-benedict-catholic-church-crisis-since/2016/03/16/id/719463/#ixzz43BO3ZZvY

Urgent: Rate Obama on His Job Performance. Vote Here Now!

Vat II has let anybody into heaven. How nice of them

LikeLike

The full text is here http://www.catholicworldreport.com/Blog/4650/full_text_of_benedict_xvis_recent_rare_and_lengthy_interview.aspx#.Vuxb5Sak8_c.twitter

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, since Bosco has brought this to light, isn’t this great. Benedict vs. Francis; Truth vs. Mercy; Dogma vs. Whatever. Scholarship vs. Off the cuff interviews. I hope Benedict has the strength to continue. Dueling popes, GREAT!

And before I get pelted with eggs, I think this is great by Fr. Blake: http://marymagdalen.blogspot.com/2016/03/now-we-have-mercy.html

LikeLike

Yes, Bosco has pointed out we now have dueling popes. Benedict vs. Francis; Truth vs. Mercy; Dogma vs. Whatever; Scholarship vs. Off the cuff interviews. Hooray, bring it on!

I thought this explanation of Truth vs. Mercy by Fr. Blake was good: http://marymagdalen.blogspot.com/2016/03/now-we-have-mercy.html

LikeLike

Jessica – by the w ay, all this ‘I’m happy to leave it up to God; it’s above my pay grade’ is unbiblical and a bit of a cop-out.

When God was so angry with the Israelites that he was about to destroy them from the face of the earth, Moses didn’t say ‘oh this is above my pay grade – I’m happy to go along with whatever you decide, Oh God’. No; Moses was horrified and interceded before God on behalf of the Israelites.

This is very much our business; we’re called upon to follow the example of Moses, to intercede on behalf of others.

LikeLike

I wonder how much of what goes wrong in our relationships with other Christian comes from thinking we have the call Moses had? Is this a man thing? I am a simple handmaidof the Lord, and if I can manage to live up to the injunction to forgive my enemies, I feel that’s quite hard enough; no need for me to compenate for not being able to do that by acting like I think I have the calling from God Moses had. Do you really think you have been called by the voice in the burning bush?

LikeLike

Jessica – ask yourself why you write this blog. What are you trying to achieve by it. Is it not your way of reaching out and trying to bring people to salvation? If so, then it must bother you (at least to some extent) that there are people who have rejected God. It bothers you enough at least to write this blog.

As Christians, we are all called to do whatever we can to bring people to Christ and it certainly should bother us when people, particularly those close to us don’t seem to be interested and seem to be going down the wrong path, away from God.

We should be earnestly praying to God for such people, praying that He will bring them to himself, praying that He will bring them into the same communion with Him that we have; it simply will not do to say, ‘oh this is above my pay grade’ and nonchalantly leave it up to God to cast them into the lake of fire.

If your starting point is Ephesians 2v3 ‘we were by nature children of wrath, even as the rest’, you thank God for what he has done for you – and your earnest desire is that He does the same for everybody else who was a child of wrath as he has done for you. You do get bothered by this, you don’t cop-out with a ‘this is way above my pay-grade’.

This is basic Christianity (any denomination or any shade).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course I pray for others – all the time. But I make no claim to be Moses or to do what he did. I write on why love matters, because I think it incomparably the best way to get people interested in God. I’ve not, myself, found that telling non-Christians they are miserable sinners and will die and go to hell, much of a draw – and I’ve heard many a Scotsman say as much. Perhaps it works in Scotland? But looking at church attendance, it seems even Knox’s country has lost patience and interest. God tried love first, we tend to try it last – but then we are miserable sinners.

I simply see myself as a handmaid, doing what little my talents can in the vineyard to the Lord. Some harvest the grapes, I’m the girl bringing round the water gourd 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jessica – you do seem to be good at reading in that which is not there – and the last time you did this, you elicited some well deserved responses which made you want to give the whole thing up.

I think you should have probably worked out that I don’t go around berating people; I don’t go around telling them that they are miserable sinners; I take people as I find them. If you infer anything else, then it says a very great deal about you.

For the record – I believe that I have not forgiven someone ‘from the heart’ if I don’t earnestly want to see them in the heavenly kingdom and am not praying that God transforms their heart and mind and brings them into communion with Him. That is my benchmark for forgiveness. If you regard their salvation as ‘way above your paygrade’ then you haven’t really forgiven.

LikeLike

We must agree to disagree. I do not know that feeling – I forgive as freely as I am forgiven; if you can’t, why can’t you? If you have not forgiven them, you are the only one effected by this. Why would you not forgive someone and let them carry on having house room in your head and heart?

LikeLike

Jessica – unfortunately, this has nothing to do with agreeing to disagree – and everything to do with you failing to address points raised, bit instead raising irrelevancies. I’m probing to find out what you really mean by ‘forgiveness’ – you don’t respond to this, but instead go on the attack with things that weren’t in the discussion and seem irrelevant.

It’s probably better to break it off – but not because of disagreement.

LikeLike

You seem not understand the simple act of forgiving – when you find a way off your high horse, it is there through Grace – perhaps you lack Grace?

LikeLike