Tags

Catholic Church, Catholicism, Christianity, Faith, Jesus, love, sin

How God calls us is not in our power. One of the great mysteries of our faith is its existence in some and its absence in others; for that I have no explanation. I don’t find the explanation that those of us who have the gift are the ‘elect’ and those who do not are not, a convincing one, but then I don’t have any other to offer; I accept it, as I do so much else, as a mystery – as Newman suggests one ought.

There are those who will claim to know who is ‘saved’ and who is not; since Scripture tells us that is a matter known to God alone, one can only tell them this and when they persist, do so seventy times seven – after that – indeed before it – silence descends.

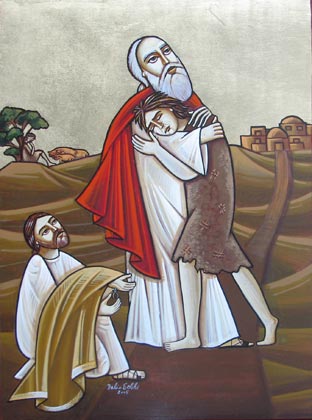

The great mystery of our faith is explained to us in heart-rending manner in the parable of the Prodigal Son. The Father loves the son. He gives him what he wants, he lets him go his own way, but when the son comes back, the Father is there and runs toward him and welcomes him back. The elder brother may be right royally displeased. Perhaps he was the perfect son and had done nothing wrong his entire life, but in his niggardly attitude toward his brother’s redemption, he showed a want of charity. There is, in all of us, something of the elder brother, so we can understand and even empathise, but the message from Jesus is clear – there is more rejoicing in heaven over the one lost sheep who is now found, than over the sheep safe in the fold. That does not mean the Father loves one sheep more than the others – just that he had lost one of his loved ones, and has now found him. Which of the fathers (or indeed the mothers, sons and daighters) among us cannot sympathise?

We do not know anything more than we are given in the parable. We cannot know why one son is good, straight, honourable and hard-working, and the other is a bit of a brat; but we see it often enough. The fault lies in ourselves, we err like lost sheep, we go astray; we sin. Often enough we do not really mean to, and we know that the road to sin is a broad one with many openings, down which we can be easily drawn. The Prodigal is attracted to the things his wealth can buy him, but he finds, as do all who take that route, that when the money runs out, the ‘friends’ are the next thing to depart. Not one of his new-found companions cares what happens to him. This occasions sadness but no surprise – like him they are worshippers of hedonism, and they have moved on to the next rich man with money to spend. So the Prodigal goes back home, chastened, knowing he has lost any claim on his father. But thinking he still knows everything, he is ignorant of what will save him – his father’s love.

Yes, to those labouring in the vineyard all day, and to those elder sons who work streadily, there is something galling about the spectacle of the later-comers being rewarded, or the Prodigal forgiven, but they should also take something away from the stories. The Father’s love is not partial, it is not the case that if it goes to the Prodigal there is less for them. The Father’s love offers them a lesson too. It is not by works we are saved; it is by Grace and Mercy. If the faith which God’s love for us calls from us is real, the works will be there.

We are loved in a way which commands only awe and gratitude. He hung and suffered there for me. Amazing Grace indeed!

“We are loved in a way which commands only awe and gratitude.” Indeed so, but should we also not add a spirit of obedience? Even if we cannot follow the rules of the household without failing from time to time, should we not try to the best of our willpower? To follow our own desires leads to our destruction and those who are wise see this and return to the household they left where the rules and the disciplines of this household are in and of themslelves grace and mercy. Grace because you are loved unconditionally and mercy because the rules of the household are ordered to will of the Father and for the good of its sons and daughters.

Far too often in this post Christian era, mercy is seen as an excuse to continue in our own desires and we extend this idea to disobedience itself though many do not realize that their heart is far from the spirit of being in communion with the household and the Will of the Father. If we fail, though continue in a spirit of obedience and trust that our Father loves us and gives what is best for us, then we are likely to receive mercy and grace to overcome that which separates us from Him. If not, then we are not present with Him in any significant way . . . for our hearts and minds are still in the world . . . and our Loving Father will allow us that freedom though He knows that within that path lies sorrow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t see how true faith and gratitude can come out anywhere but where you describe. Real faith cannot but draw us towards the real heart of obedience, which is to love him and to want to do his will. I can’t see any other outcome 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nor do I, C. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t you simply stand in awe of the wisdom which gives us the Prodigal parable? The more one prays on it, the more it gives – simply one of the many examples of the sheer depth of what Jesus offers us 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed it does. I could write a number of posts that would differ from each other and yet not contradict each other. It is a marvel. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are times it is overwhelming – what it must have been like to have heard those stories for the first time from his lips! Yet, would we, I wonder, have been any wiser in our reception at the time than the Apostles? I guess not 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe that they thought on these the rest of their lives . . . pondering them in their hearts as did Our Lady and the things that she experienced. I’m sure that they grew as we all do in their understanding and wisdom without exhausting the possibilities.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed – and after the resurrection, so much was clear that had been clouded – they then saw clearly and not through the glass darkly; so it will be for us at the last 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Our true conversions are usually a bit like a small pentacost it seems to me. We are sent these moments and they seem most mysterious as to when, where, how and why we had arrived somewhere we had not even imagined. I suppose that is how fishermen who ended up where they did must have felt. Awe, mystery and the presence of a supernatural grace that led them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As, we pray, it will us in our turn 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

With faith, hope and charity we might well receive the same reward. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

now a different take. What about the Father is this parable? Though he loved the son that was loyal to him, the son didn’t know that he was loved. So the fault lies with the Father.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The fault lies in the elder son’s lack of faith that the Father always acted in the best interest of the family and him. It sometimes requires a falling out, suffering or a sense of abandonment which opens up the riches that we take for granted and for which we give no thanksgiving for. What we already possess we sometimes don’t properly value.

The prodigal son, however, who came back home shows us so much: sorrow, contriteness, a swallowing or abandonment of his pride and his eventual, hard-won, humility; which is the foundation of any true holiness.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No, the fault lies with the son, who is too eaten up with self-regard to see that he, too, is loved – which is why the father tells him so, as he sees that too 🙂

LikeLike

The implication is that the Father lacked effective communication with the son.

LikeLike

With due respect David, that is modern pyschobabble. The Father is God, and the idea that Jesus was really telling us that God does not understand us does not stand up to scrutiny.

LikeLike

That maybe true yet from a different point of view at least it made you think slightly. The text for me is insufficient.

LikeLike

It did, David, but we cannot, I think, argue that God, the Father, does not effectively communicate with us – although we can, and I would, advance the argument that, like the eldest son, we do not listen and tend to sulk and blame God when it is our fault 🙂

LikeLike

In real life, it’s the parents responsibility to make sure that their children know that they are loved not the other way round. This is made difficult because we’re not God and the various personality types come into play.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I see in this parable a type of Adam before the fall, in the elder brother and of Adam after the fall, in the prodigal son . . . and thereby an anology for all of us. The ‘fatted calf’ is not dissimilar to the sacricial lamb or holocaust for sin and the joy in the release of sin by the sacrifice of the Real Sacrificial Lamb which was to come . . . Jesus Himself.

It is said but that our sin actually opens up for us the depths of God’s mercy and love which could not know by any other way. Thus, “O, Happy Fault.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

***sad not said***

LikeLike

“There are those who will claim to know who is ‘saved’ and who is not; since Scripture tells us that is a matter known to God alone”

Which scripture are you using? I John 5;13 says

These things have I written unto you that believe on the name of the Son of God; that ye may know that ye have eternal life, and that ye may believe on the name of the Son of God.

Heres the deal. The saved know they have met Jesus and are different. So how can they tell another fellow pilgrim? When they start talking to each other. Their stories are pretty much the same. You, well, I mean we, can tell they know Jesus personally by how they refer to him and what hes done. Its like two people discussing a mutual friend.

LikeLike

No, that is your man-made misinterpretation of the book the Church canonised. Of course we know that Jesus died so that we should have eternal life, but we also know, that like St Paul, we have to continue to run the race, not sit on oiur duffs thinking that salvation is a one-off. It is clear from Scripture that it is a proceess – see here for a full list of scripture: http://www.ewtn.com/library/ANSWERS/PASTPRES.htm

No, if you want to engage with that list and explain why it does not mean that we have been saved, we are being saved, and, if we remian true to the last, that would be good. Simply parroting your misunderstanding is no good.

Scripture calls you out, now deal with it, or be quiet.

LikeLike

“And not only they, but we also who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, eagerly waiting for … the redemption of our body.” (Romans 8:23)

Heres one on the list. Redemption of our bodies. Its the soul that is saved.

One can view salavation as a future even. I have no trouble with that. Saved from the wrath to come. Its just semantics at that point. Even as your EWTN points out, many scripture talks of salvation as a past event. Yeah, its when one is born again. So, one can consider the actual saving happens when we, the saved, are taken from the earth befor the wrath comes.

Bottom line is, open the door and sup with him now….then philosophize all you want.

LikeLike

So, here we go. No one, no one at all, is disputing that the blood of the Lamb saves us, and that in receiveing him by faith, we are saved. The question is what next?

Do you believe (as some of the Corinthians did until Paul told them otherwise) that being saved means you can do anything and never lose your salvation? That’s not semantics – if it had been Paul would not have bothered.

Paul says we have to work it out in ‘fear and trembling’ – that is clear enough. If being saved was a once off, why the need to keep running and trying?

No philosophy here, all Scripture, and you still can’t engage with it. Scripture defeats you, as it does all man-made attempts to lie about what it says. It nowhere says that once you have received Jesus you stay saved forever. If you believe that, you have accepted another gospel than Christ’s.

LikeLike

Great link C. All here should read and study it, then come back for a real good discussion. And, I encourage all those that may usually just read and not comment, to do so. This article and C’s link is a great place to start commenting and join in.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Steve – much appreciated.

LikeLike

“And do not grieve the Holy Spirit of God, by whom you were sealed for the day of redemption.” (Ephesians 4:30)

Heres another verse from EWTN site. As I mentioned, the act of being saved is future. One purchases a apple, then the vendor hands it to you, then you eat it. Three step process.I don’t see where my”interpretation” is flawed. I don’t need an interpretation. I let the good Shepherd do my battles. People who stand on the outside looking in need an interpretation, cause they have no idea what born again is.

LikeLike

Agan, no one is arguing that we are not sealed with his blood. The argument is over whether that is a one-off event which guarantees us eternal life whatever we do. That is where what you say is flawed – you seem to think that once you received Jesus that is the end of it. It isn’t, you can lose salvation by falling for the oldest of satan’s tricks – which is telling you you are fine now and can d what you want.

You are the one standing outside the Church Christ founded trying to tell us what the book it canonised really says. Really, what a joke!

LikeLike

8Can one lose their salvation? Hmmmmmm. Im going to say that one can lose their salvation. I cant rule that out. As long as one is convicted about what they are doing wrong and repent, salvation is still there.. The born again are different that befor they were born again, so lots of things they used to do routinely, they don’t do, hopefully, as much. Some come around full circle.

Now, peple here bring up”working out your salvation with fear and trembling”. It doesn’t say building up salvation. One has to be saved in order to work it out. Yes, when one is born again, at that instant he is saved, totally.100% There is no partial salvation.

My advice is….get saved, and then talk about it. That goes for me too.

LikeLike

What are you talking about? No one here wrote about ‘partial salvation’ or ‘building up’ salvation.

LikeLike

Its Saturday, ..I cant hog the computer.

LikeLike

Pingback: Misunderstandings? | All Along the Watchtower

There is a wonderful painting on this theme by Rembrandt in the Hermitager in St Petersburg.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it is very evocative and moving.

LikeLike