Tags

What holds a society together? That wasn’t the sort of question you needed to ask before the advent of democracy. The upper orders ruled, and if the lower orders got out of hand they could be dealt with by force, or, if necessary, force and guile. In this country there was also a set of shared values mediated by the church, or, after the Reformation, the C of E, and even those who rejected that church, accepted the Christian values it embodied to society at large. The Ten Commandments were acceptable statements of fact, as well as a set of aspirations which, for the most part, had the backing of the law (you could never be made to honour your father or your mother, and coveting your neighbour’s ass, as long as you did nothing about it was between you and God).

What holds a society together? That wasn’t the sort of question you needed to ask before the advent of democracy. The upper orders ruled, and if the lower orders got out of hand they could be dealt with by force, or, if necessary, force and guile. In this country there was also a set of shared values mediated by the church, or, after the Reformation, the C of E, and even those who rejected that church, accepted the Christian values it embodied to society at large. The Ten Commandments were acceptable statements of fact, as well as a set of aspirations which, for the most part, had the backing of the law (you could never be made to honour your father or your mother, and coveting your neighbour’s ass, as long as you did nothing about it was between you and God).

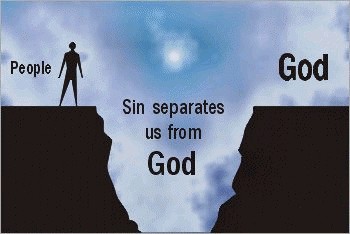

Other things followed from such a consensus. It was accepted that unless you happened to inherit wealth, you worked for your living, and if you didn’t, or couldn’t, things were tough; charity, and latterly the State, would intervene to protect the most vulnerable; the family was the basis for a stable society, which allowed women the space to bring up children whilst the father earned a living for them all; marriage was one man and one woman, preferably for life, and getting out of a marriage was not an easy thing to do; if you got a woman pregnant, you were expected to do the ‘decent thing’, which was not defined as killing the baby because it was ‘unwanted’.There were two sexes, men and women, and for every ‘right’ society afforded you, a ‘responsibility’ went with it. These, and sets of other unspoken assumptions, held society together. There was, latterly, an assumption that these values were so universal that they could survive if their underpinning – Christian belief – was eroded. Is that looking secure?

This translates into attitudes towards our leaders. As we were never given the opportunity to vote on same-sex marriage, or on the consequent mangling of our language, where ‘husband’ can be male or female (or neither) and ‘wife’ likewise, we shan’t know whether ‘we the people’ would have approved or not; in similar ways, things like abortion, easier divorce and the legalisation of homosexuality, were decided without consulting us. The effects of these things now work their way through our society. Our leaders are content, but to many of us outside the Metropolis, it seems as though we are out of touch with their mind-set; the problem is we don’t have enough trust in them to accept that they know best; there’s too much evidence that they behave in ways designed to mislead us. A Government which will take us into a war on a false prospectus, as Mr Blair’s did, betrays a vital covenant. ‘Thou shalt tell no lie’ is not something we expect a politician to keep in all circumstances, but it is one we expect to be kept on the big things.

It wasn’t that in the good old days we thought our politicians were honest, decent Christians, but it is that we thought they shared the same values as we did and could, therefore, in some real way, ‘represent’ us and our views. After all, many of them had careers outside politics, and even if there was always a core cadre of careerists, there were plenty of back-benchers who were men and women of note locally who did not look to be Ministers, or for Ministerial patronage.

Moreover, many of our politicians clearly left politics poorer than they would have been otherwise. Churchill could have earned very large fortune after 1945 if he had concentrated on it, but while he did write his best-selling memoirs, he soldiered on as leader of the Opposition, and then another term as Prime Minister; it meant his family had to hand over his beloved Chartwell to the National Trust, because he was not a multi-millionaire, but that was the price he was willing to pay. Nowadays, they cut, run, and make a pile, as though they know it is all going to end soon. We should trust such men precisely why?

So, with trust between governed and the government at all-time lows, and with a loss of shared values, where next?

All this multiculturalism stuff in USA is uncomfortable . This is a nation of immigrants, my own ancestors hailing from Spain, Sicily and Rome. But European immigrants of the last two centuries assimilated. In Miami Dade Country there are enclaves wherein learning English is not necessary as the Spanish and Haitian communities are self sustaining as self promoting to a large degree. Miami Dade County is now 80% minority and over 50% foreign born. There are no historical , religious, or literary common denominators anymore it seems to me. There are very few in attendance now at Veterans Day or Memorial Day events and as a consequence fewer and fewer are held. But Cinco de Mayo and Jamaican Goombay are flooded with attendees and few here know what St Patrick’s Day or Columbus Day is except descendants of Europeans in the north and midwest of America. No sense of we and us or national consciousness or corporate consciousness as contrasted to relatively single race or ethnicity countries like Japan or Sweden for instance.

LikeLike

That seems an unwise policy, and certainly not the one formerly pursued in your country Carl. Social cohesion without shared values is impossible.

LikeLike

It’s always taken a generation or two but people coming here knew that they would have to work hard and eventually learn English and all that, or they would starve. In a sense it was a force assimilation but assimilate they did, German Anabaptist, Irish Catholic, Chinese Confucian. Get over it and get to work or you ain’t eating. A hard world perhaps, but a just world, and one that worked to build a society.

What we have now (on both sides of the Atlantic, near as I can tell) not so much.

LikeLike

I agree, Neo, not a good omen for a shared future.

LikeLike

That it is not. I’m increasingly concerned that it all going to go a glimmering.

LikeLike

The wrong sort of politicians Geoffrey. Read this:

http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/news/douglascarswellmp/100232722/conservatism-is-in-retreat-heres-why/

LikeLike

They are indeed Strauns. As the thing has become professionalised, the stakes for the politicos has got higher, as it is the only job they have.

LikeLike

I agree completely, although I know ours better, same problem. When your first job is political and that become your career, you’re no longer serving your constituents, you’re serving yourself. Easiest way to get rich in America, get elected to Congress. Jess reminds us periodically that Churchill and Truman both came out of office poorer than they went in, which doesn’t happen anymore.

For my self, I always remember what george II said upon being assured that Washington wouldn’t run for a third term, “Then he shall be the greatest man in the world.” We need more of them.

LikeLike

Yes, that act of Washington’s did indeed set the seal on his greatness. He was a true Roman of the old Republic. Sad we shall not see his like again.

LikeLike

It does seem unlikely but, I’m sure the Romans said it too, so it can happen.

LikeLike